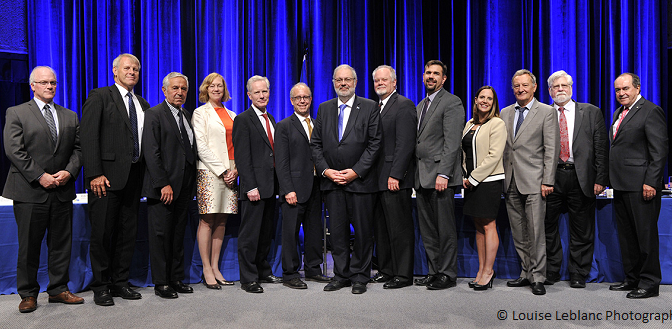

On 15th June 2015, Philip took part in a public consultation on the energy strategy of Canada’s Quebec Province, in a session focused on hydrocarbons.

The full context of this review is available at: http://www.politiqueenergetique.gouv.qc.ca/themes-2/hydrocarbons/

A video of full event is available at: http://webcasts.pqm.net/client/mrn/event/1546/fr/

with my own intervention at 1 hour 49 minutes.

The formal text I submitted in advance of the event is below:

Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources of Quebec

Expert Panel- Hydrocarbons, Governance

Summary of presentation

Philip Andrews-Speed

Governance encompasses the processes and actors involved in the formulation and implementation of strategies, policies and rules. In a democracy, such governance involves a wide range of actors and has to take account prevailing values and norms as well as the interests of minority groups. Given the nature of the strategic decisions to be made relating to hydrocarbons, all citizens of and organisations in Quebec must be involved (directly or indirectly) in the decision-making process. In some cases it will also be necessary to involve actors in neighbouring provinces and states. I divide this analysis into two parts: the strategic decision, and the governance framework for hydrocarbons.

The Strategic Decision

The strategy document for hydrocarbons appears to promote the idea of developing onshore and offshore oil and gas reserves as an important part of provincial energy policy. This proposal should be questioned. Designing energy policy involves prioritising and making trade-offs between 4 sets of objectives:

- Security of supply;

- Cost competitiveness of energy sector;

- Environmental protection;

- Access to energy/energy poverty.

In its strategy document, Quebec has identified the first three of these. Under the heading ‘energy security’, I think it is necessary to question the strong emphasis on needing to reduce the province’s high level of import dependence for oil and gas. The North American continent has vast reserves of conventional and unconventional oil and gas, and much of these lie in Canada. The risk of sustained interruption in supplies is low. Whilst the impact on balance of payments may be significant at times of high (oil or gas) prices, the development of an entirely new hydrocarbon industry may not be the most appropriate and acceptable way to address this challenge.

In addition, the document highlights the importance of industrial policy on account of the need for oil supplies to feed the petrochemical plants. Whilst it is clearly desirable to sustain the petrochemical industry in Quebec, it is necessary to question whether this requires promoting hydrocarbon production within the province. Given the abundance of natural gas in Canada and the USA, the petrochemical industry could be gradually transformed to draw on gas as a feedstock rather than oil. This would also support environmental objectives.

The document also identifies to potential benefits to be derived from hydrocarbon production in terms of employment, spin-off industries and fiscal revenues. However, as the report acknowledges, the likelihood, timing and scale of these benefits are all unknown.

In summary, the broad strategic question for Quebec is whether it wishes to keep the energy sector reliant on hydrocarbons by promoting oil and gas development, or whether it should progress the transition towards a cleaner energy mix by reducing the share of oil in the mix and increasing the use of natural gas, biofuels and different forms of clean electricity. In the light of the importance to Quebec of the knowledge economy and the richness of the ecosystems, the arguments in support of developing hydrocarbons will have to be very persuasive if they are to gain widespread public support.

Designing the governance framework

Capacity

As acknowledged in the strategy document, a key deficiency in Quebec’s governance capacity arises from the lack of experience with hydrocarbon development, beyond the recent and current low-level exploration. This weakness affects government, industry and civil society. In order to ensure that good oilfield practice prevails from the start, it will be necessary to ensure that the all companies involved in hydrocarbon development have the requisite expertise and experience and that all the relevant government agencies are properly resourced. More difficult will be the task of building understanding of the hydrocarbon industry in civil society organisations and in society as a whole. For these reasons it is essential that the exploration and possible development of hydrocarbons starts slowly.

Offshore hydrocarbons

For the sake of simplicity, I assume that offshore hydrocarbons will be mainly conventional. The principal governance challenge here will be with respect to safety and the environment and arises from a combination of the rich ecosystem, the heavy shipping traffic, the semi-enclosed nature of the St Lawrence Estuary and the Gulf of St Lawrence and the presence of other Canadian provinces around the Gulf. As acknowledged by the strategy document, the impacts of an oil spill would be substantial.

Onshore hydrocarbons

The onshore development of conventional hydrocarbons can be carried out in a manner that is very sensitive to societal and environmental concerns. An example is the Wytch Farm oil field in southern England which is the largest onshore oilfield in Western Europe. It lies in an area which includes a World Heritage site, sites of special scientific interest and areas of outstanding natural beauty (see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wytch_Farm). It also lies close to two towns (Poole and Bournemouth) which have large populations of wealthy retired people who live there on account of the beauty of the area. Acceptability was achieved through a combination of tight environmental regulation, considerable expenditure and horizontal drilling.

Unconventional hydrocarbons are a completely different matter. On account of the nature of the resource, extraction has to occur across a wide area, and drilling and fracturing activities roll across the countryside like an army on the march. In order to sustain high levels of production, hundreds or thousands of wells have to be drilled each year in a single basin. The industry continues to take steps to minimise the environmental risks that have been well documented in the USA and elsewhere. Nevertheless, the distinguishing feature of unconventional hydrocarbon production is the physical disturbance to the landscape and society, despite the technological advances that are allowing more wells to be drilled from a single location. As a result, the key governance challenge for government and companies is to win the social license to operate, and the government must take the lead in this.