China’s consumption of coal fell in 2014 for the first time in since the 1970s. The exact scale of the decline remains open to interpretation, with different sources reporting different figures on account of the difficulties in obtaining reliable statistics on coal consumption. Estimates suggest that consumption in 2014 fell by between 0.4% and 3.0% from a peak of around 3.8 billion tonnes in 2013. Domestic production also fell by as much as 2.5% from about 4.0 billion tonnes. The decline in demand had a disproportionate effect on imports which fell by 11% to 291 million tonnes in 2014.

These trends have continued into 2015, with coal consumption in the first four months of the year being 8% lower than in the same period in 2014. Production of coal was down 6% and imports down 38% year-on-year. The figures for May 2015 show that imports were down 40% compared to last year.

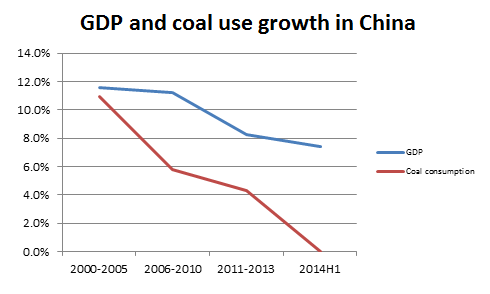

This decline in China’s coal consumption arises from a combination of trends in the wider economy and in the energy sector. A key point is that coal is the swing fuel in China on account of the abundance of low cost reserves. Statistics for the last three decades show that the rate of growth of coal consumption is closely correlated with the rate of growth of GDP. This causal relationship results not just from a simple link between GDP and energy demand, but also from the way energy intensity increases at higher rates of growth, for the intermittent surges in GDP growth have generally been triggered by programmes of investment in infrastructure such as we saw in the early 1990s, from 2003, and in 2011.

China’s annual rate of economic growth has slowed from more than 10% in 2010 to 7% or less in 2015. This is a consequence of reduced demand for Chinese goods around the world and the reluctance of the current leadership to boost economic growth through yet another stimulus package. The lack of investment in energy intensive industries such as steel, cement and plate glass, has allowed the structure of the economy to move towards the better balanced that the government seeks, and this in turn has caused a significant decline in the rate of increase of energy demand. The country is also benefitting from the energy efficiency campaign launched in 2004 that achieved substantial efficiency gains in the energy intensive industries. In 2014, the consumption of primary energy rose by just 3.8% and electricity by 3.6%, the lowest rates of growth since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s.

The other main source of the decline in coal consumption lies within the energy sector itself, where a rapid change of fuel mix in the electrical power sector has been a direct result of the government’s strategy to reduce air pollution from coal use. The most reliable data for 2014 is from the electrical power industry. This showed a marginal decline of an estimated 1.6% in total electricity output from coal-fired power stations. Average utilisation rates fell from 57% in 2013 to 54% in 2014. Improved thermal efficiencies allowed the total use of coal in power generation to fall by 2.5%. The decline in coal-fired power generation was more than offset by other sources, most prominently by additional hydropower delivered through new capacity as well as favourable weather conditions. In addition, the country’s massive investment in wind, solar, nuclear and biomass energy allowed non-fossil fuel power generation to grow by as much as 19%. A final factor in the decline of coal consumption lies in the apparent slowdown in development of coal gasification and liquefaction projects on the grounds of their intensity of water use and poor economic viability.

The outlook for China’s coal consumption over the next year or so depends critically on whether the government decides to boost economic growth through a new infrastructure programme. If it does, then coal consumption is certain to rise again. In the absence of a stimulus package, the short-term outlook for coal demand within the power sector depends on how well the weather supports hydropower generation and on how rapidly wind, solar and nuclear power grow. Over the next ten years, hydropower and wind energy are seen as the main substitutes for thermal power, with nuclear, solar and natural gas playing a supporting role. This should allow coal use in power generation to peak by 2020 and would have significant consequences in China and abroad.

The most observable impact within China would be a sustained decline in atmospheric pollution from coal combustion, though other sources of pollution may persist if they are not addressed. Domestic output of coal will decline and this production is likely to become increasingly concentrated in the hands of a small number of state-owned mining enterprises operating a declining number of large-scale mines. This, in turn, should lead to a sustained increase in mechanization, with consequent improvements in safety and environmental standards. The downsides would include the loss of employment in some coal mining districts, unless new industries are developed, and a possible greater need for coal transportation as only the most economically viable mines remain open.

The good news for the rest of the world would be the continuing decline of carbon dioxide emissions from China’s energy sector which would make a major contribution to global emissions reduction. The main losers are set to be the overseas mining companies which have invested in new coal mine capacity in order to meet an anticipated sustained demand from China. At the beginning of 2015, these companies were already facing Chinese restrictions on the import of low quality coal. This constraint has now been exacerbated by laborious quality control inspections at ports. Australian coal producers, in particular, could find themselves with excess capacity, as is the case with LNG export terminals. India’s demand for coal will continue rising, but the current government seems determined to meet this demand form domestic production. If both China and India are successful in implementing their respective policies, then international coal prices are set to remain low for some time.

There are two key uncertainties in this outlook. The first is whether the government can resist the temptation to boost economic growth by launching yet another stimulus package that would drive up coal demand. The second is whether the growth of non-fossil fuels matches expectations. If it does not, then coal will fill any emerging gaps in the supply-demand balance.